Paradoxes

- “This statement is false”

- “I am nobody”

- “A man goes back in time and kills his grandfather”

If the man killed his grandfather, his father wouldn’t have been born and hence, the man himself wouldn’t have been born to go back in time and kill his grandfather🤔. If you are scratching your head for this itself, be ready for some more hair scratching. All the above are examples of what is called a paradox.

A paradox is any statement or proposition that seems self-contradictory or absurd but may be proven to be true.

Let us look at a few interesting paradoxes in the field of mathematics.

Russell’s Paradox

The most widely known paradox in mathematics is the Russell’s paradox which was discovered by Bertrand Russell in 1901.

Russell’s paradox is a counterexample to naive set theory, which defined any definable collection a set. The set of all natural numbers, set of all people living in India etc. We can describe the collection of numbers 1, 2, 3 by saying that x is a collection of integers between 0 & 4. Writing it formally, x = {n: n is a integer and 0<n<4}. It need not be necessarily numbers. We can define a set y = {n: n is a resident of India}

Let X be the set of all sets that are not members of themselves.

- If X is not a member of itself, then X is a set that is not a member of itself and hence, is contained in X, which is a contradiction.

- If X contains itself, then, X is not a member of itself(according to how X is defined), which is contradictory. This contradiction is Russell’s paradox.

If you find it difficult to understand this, let me give you a simple example which is similar to the above paradox, known as the Barber’s paradox:

“A barber is a person who shaves all those who cannot shave themselves. The question is, does the barber shave himself?”

Answering this leads to a contradiction. The barber cannot shave himself since, he only shaves those who cannot shave by themselves. Subsequently, if he did not shave himself, he falls into the category of people who cannot shave by themselves(and hence, require a barber) and him being a barber, must shave himself.

Russell’s paradox was eventually resolved by an axiomatic set theory called ZFC, after Zermelo, Franekel, and Skolem, which gained widespread acceptance. ZFC’s resolved the paradox by defining a set of axioms in which it is not necessarily the case that there is a set of objects satisfying some given property, unlike naive set theory in which any property defines a set of objects satisfying it[1].

Hilbert’s Hotel Paradox

This was a paradox devised by German mathematician David Hilbert in the 1920’s to demonstrate how difficult it is for us to understand the concept of infinity.

You are the manager in a hotel which has infinite rooms and all the infinite rooms are occupied. A person comes to your hotel and requests for a room. You cannot turn down a customer right? So, what do you do?

Simple. You ask all the guests to shift to the adjacent room.

The guest in Room 1 goes to Room 2, the guest in Room 100 goes to Room 101 & the guest in Room 17942134 goes to Room 17942135. This leaves Room 1 free for the new guest to occupy. This method can be applied for any finite number of guests that arrive. (If 20 guests were to arrive, you just need to ask all the guests to shift by 20 rooms)

Now, a bus consisting of an infinite numbers of tourists turns up. What do you do?

This is also simple. You ask all the guests to shift to the room number which is twice of their existing room.

The Guest in room 1 goes to Room 2, the guest in Room 5 goes to Room 10 and so on. (Well, easy for them, but not for the guest in Room 824302!!!😰). This leaves an infinite number of odd numbered rooms free for the new guests to occupy. Well, you thought, that is it right?

Let us up the game a little. What if an infinite numbers of buses carrying an infinite number of tourists turn up?

There are many ways to solve this, I will explain one of the simplest methods here.

Euclid comes to your rescue here. Around 300 BC, Euclid proved that there are infinite number of prime numbers(2,3,5,7,11,13…..). Making use of this:

- You go the guests in your hotel and ask them to shift to the room number that is equal to 2 raised to their present room number i.e Guest in Room 1 goes to Room 2, guest in Room 2 goes to Room 4, guest in Room 3 goes to Room 8 and so on…..(Luck guy in Room 1. He has to shift only one room whatever the situation). In this way, all the powers of 2 are filled.

- Now, you go to the first bus and tell that “Occupy the room that is 3 raised to the power of your seat number”. 1->3, 2->9, 3->27 ……. All the powers of 3 are filled.

- You go the second bus and tell them that(you should have figured it out ourselves by now) to occupy all the powers of 5

- In this manner, you allocate one prime number to each bus.

For a pictorial representation, you can refer the pic below

Hope you understand that, in this method, no rooms overlap and all the infinite passengers in the infinite buses are tucked in comfortably along with the already existing infinite guests.

You might be surprised to note that, even after accommodating infinite number of buses with infinite passengers, there are still some rooms that are vacant. Yes. Rooms with numbers 6, 10, 12, 14 etc are still unoccupied since they are neither primes nor higher powers of any prime numbers. (Maybe you would want to take one room😜)

But trust me, I have only explained a fairly easy solution. There are other complex solutions. And I have not yet gone into real numbers and fractions: rooms with numbers 1/2, 1/4, square root of 2, and the guest in room number “pi” who demands an endless supply of dessert!!!

The Hilbert’s paradox can be classified as a veridical paradox i.e a paradox whose results appear to be absurd at first glance, but can be demonstrated to be true.

Another example of a veridical paradox is the Monty Hall problem about which I have discussed in detail in one of my previous posts.

2=1???🤔

Yes. There are many ways to show that 2=1, one of which I have shown below(Taken from The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel, Pg 222):

It seems correct right? But it shouldn’t be. So where is the mistake?

In the first step, we have taken a=b. So, a-b=0. When we divide both sides by (a-b) in Step 4, we are actually dividing by zero, which is illegal in mathematics. Hence, the proof is wrong.

Such paradoxes are called falsidical paradoxes i.e paradoxes which not only appear to be false, but are also actually false due to a mistake in their demonstration.

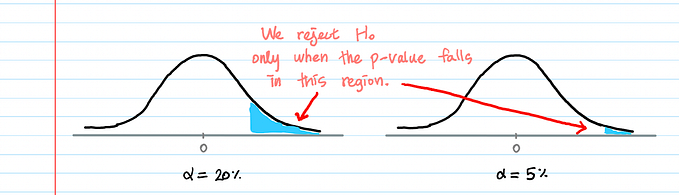

Let us next look at a very famous and important paradox which can be found in the field of data science

Simpson’s Paradox

Simpson’s paradox is a phenomenon which occurs when 2 groups of data show a particular trend individually but when combined, this trend is reversed.

Consider a scenario of 2 batsmen in a cricket match. We compare their strike rates(runs scored divided by the number of balls faced) in 2 consecutive matches. In both matches, the second player has a higher strike rate. Does that mean he has the higher strike rate when combined? Not necessarily. Take a look at the table below

Player 2 had the higher striker rate individually, but when combined, Player 1 had the higher strike rate. This is due to the large difference in the number of balls faced in each match by both players.

Yes. I did cook up the above example by playing around with the numbers. But, this is not something that is only confined to theory. There are a handful of examples of this paradox in real world, especially in the field of data science.

Consider the comparison of the effectiveness of 2 kidney stone treatments. On viewing individually, it was seen than Treatment A was shown to work better with both small and large kidney stones, but, aggregating the data shows that Treatment B works for all cases.

Why does this occur? To understand this, we should look at how the data is generated. It turns out that treatment A is more invasive than B. Since small stones are considered less serious cases, doctors are more likely to recommend the inferior treatment, B, for small kidney stones, where the patient is more likely to recover successfully since the case is less severe. Hence, we see that around 270 people opt for treatment B for small stones while only 87 go for A.

However, for large serious stones, doctors prefer treatment A which is more invasive. Though the performance of treatment A is better, since it is applied to more serious cases, the overall recovery rate for treatment A is lower than treatment B.

I will discuss more such interesting paradoxes in my next post.

Thanks for reading!!

References

Originally published at http://infinitesimallysmallcom.wordpress.com on June 3, 2020.